Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson (Spiegel & Grau 2014)

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson (Spiegel & Grau 2014)

First line: “I wasn’t prepared to meet a condemned man.”

This borrowed copy, underlined and written in by my dad, has been sitting on my shelf for years. I’ll be honest and tell you that when I picked it up last week, it was not because I was in the mood for it, but because I thought I should. Should because all the books stacked on my night table that I was planning to pick up next are written by white people. Should because I haven’t been to a protest or march yet. Should because when I did my diversity audit last week I was angry at myself that I had only read ten BIPOC authors this year, only six of whom are Black. “Should” is what finally had me picking up Just Mercy. The guilt. And maybe that’s not the best reason. (I mean, I know it’s not the best reason.) But no matter the reason, I did. And, oh how glad I am.

Just Mercy is part memoir, part courtroom drama, part social commentary on racism in America, and so much more than any one of those things. Author and lawyer Bryan Stevenson shares how he got his law career started by working an internship with the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee (SPDC) in Atlanta. After a disappointing first year at Harvard Law School, this internship suddenly brought into focus what would become his life’s work and passion: helping those who had been wrongly convicted and bringing them justice.

Much of the book centers around the case of Walter McMillan, who was accused and convicted of killing a young white woman in his hometown of Monroeville, Alabama (yes — that Monroeville… the one most widely known as the home of Harper Lee) and sentenced to death. So many things about McMillan’s case are ludicrous — the jury sentenced him to life in prison, the judge overruled to give death penalty; the only evidence was that of a “witness” who entirely fabricated a story placing McMillan at the scene; dozens of other people were with McMillan at the time of the crime at an event happening at his home. The list goes on. And yet, here he was, sitting on Alabama’s Death Row, with no hope of escape until the Stevenson’s new non-profit, the Equal Justice Initiative, stepped in.

Interspersed with chapters that focus on McMillan are chapters in which Stevenson shares about other cases and issues he’s encountered through the EJI. He describes the hundreds of children ages 13-17 who were sentenced to life in prison for non-homicide crimes; he gives us the stories of people with severe mental illness and history of trauma (over 50 percent of prison and jail inmates in the United States are those with diagnosed mental illness) whose illnesses were not taken into account in sentencing; he tells us about young women who find themselves sentenced to life in prison after suffering through a still birth. Injustice after injustice after injustice. It’s nothing short of infuriating.

Motivated by Stevenson’s work, I realized I had no idea about how capital punishment is being handled in my adopted state of South Carolina. From the SC Department of Corrections, I learned that of the 282 people executed since 1912, 208 of them were Black. For those of you without a calculator in front of you, that’s 74 percent, when the percentage of Black people currently living in South Carolina is 27 percent. I also learned that while there hasn’t been an execution since 2011 (because the DoC cannot get access to the drugs required for lethal injection and prisoners have the right to choose their method of execution), last year the SC Senate voted 26-13 to make electrocution the state mandated option if drugs were not available. Earlier this spring, the House Judiciary Committee voted in favor of the bill (although removed the language adding the firing squad back in as an option), pushing the bill onto the full House. In his book, Stevenson describes the horror of electrocution that makes it clear it is cruel and unusual, and yet here we are in 2020 voting to bring it back.

The death penalty is one of those issues that can always be debated (I see you, sophomore year speech class), but Stevenson brings up a point in his epilogue that more clearly states the Con side than I’ve ever been able to articulate:

“… Walter’s case had taught me that the death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit.. The real question of capital punishment in this country is, Do we deserve to kill? … Mercy is most empowering, liberating, and transformative when it is directed at the undeserving. The people who haven’t earned it, who haven’t even sought it, are the most meaningful recipients of our compassion.”

Even if this weren’t a human rights injustice, as Stevenson clearly elucidates it is, capital punishment creates killers of us all. And while Stevenson is exhausted by the incredibly draining work he does that sometimes ends with his clients being executed anyway, he continues on because of that promise of mercy. His writing, his work, is an inspiration and certainly makes me want to DO SOMETHING with the mercy and privilege I’ve been given.

Join me, won’t you?

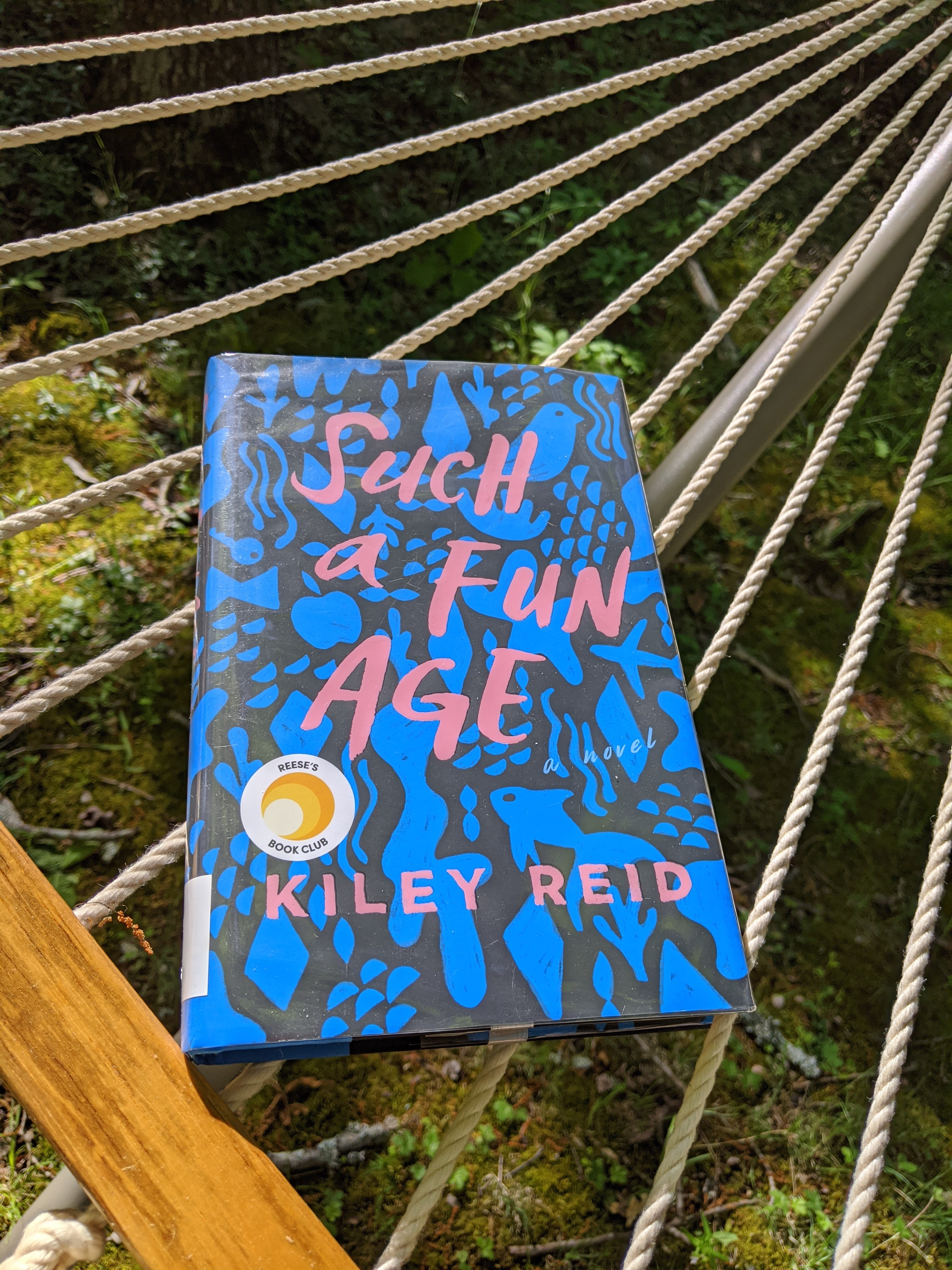

Such a Fun Age, by Kiley Reid (G.P. Putnam’s Sons 2019)

Such a Fun Age, by Kiley Reid (G.P. Putnam’s Sons 2019)